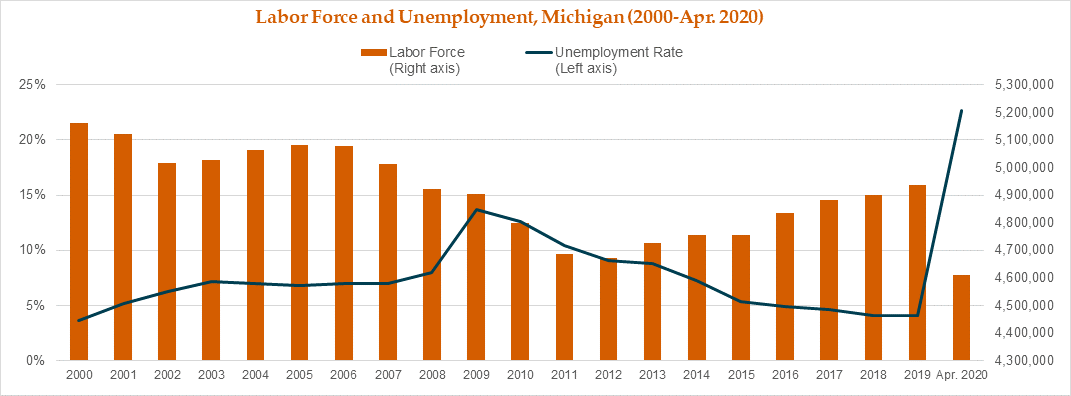

Statewide Unemployment Spikes in April

Michigan’s unemployment rate reached historic levels at the onset of the pandemic, skyrocketing by 18.4 percentage points to achieve a rate of 22.7 percent in April — the highest jobless rate seen for the state since at least 1976 (as far back as comparable records extend) — according to data released by Michigan’s Bureau of Labor Market Information & Strategic Initiatives. The spike in unemployment observed over-the-month reflects a significant decline in the number of employed residents across Michigan, which plummeted by over 1.1 million from March to April, while the number unemployed swelled by 839,00. The net effect of the pandemic’s impact on the state’s labor force in April resulted in 291,000 labor force separations, which indicates that one-fourth of residents who experienced job loss over-the-month also disconnected from the labor force (either no longer seeking work, moved elsewhere, or recently deceased).

The acceleration of unemployment observed throughout Michigan over-the-month significantly exceeded the 10.3 percent spike to unemployment seen nationwide, with the national unemployment rate at 14.7 percent in April. Michigan’s seasonally adjusted job count dropped by 1,009,000 in April to just over 3.4 million, with the greatest job losses concentrated in industries deemed nonessential and those that required person-to-person contact. April job cuts were most prevalent among Leisure and Hospitality (-58.7%; -237,000 jobs), Manufacturing (-28.1%; -174,000 jobs), and Trade, Transportation, and Utilities (-19.8%; -159,000 jobs), while industries least affected included Natural Resources and Mining (-5.4%), Information (5.5%), Government (5.5%), and Financial Activities (-6.2%).

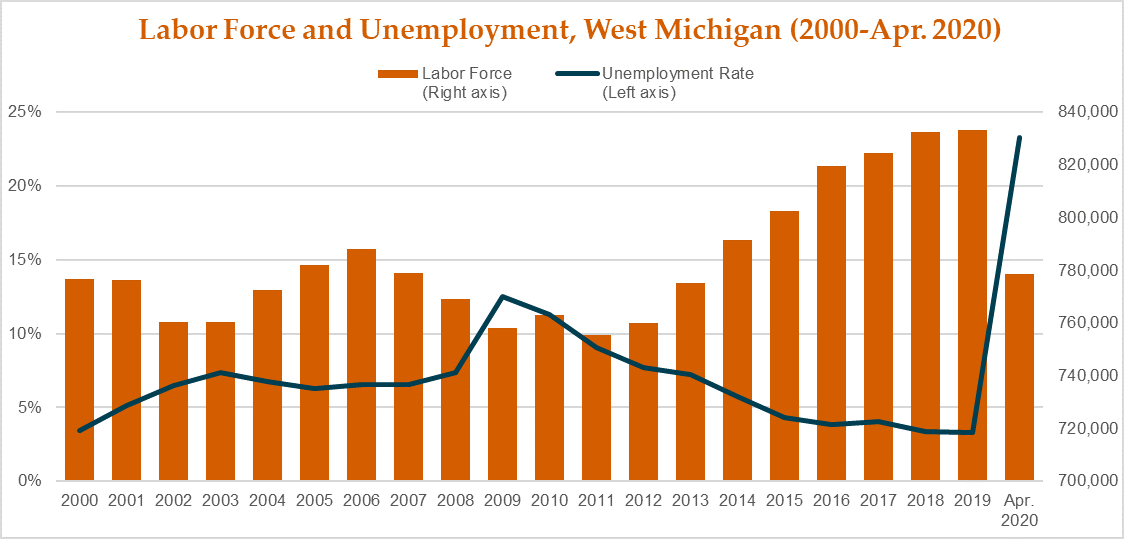

Historic Rates in West Michigan

Adhering to the trend observed across the nation, the 23.3 percent rate of unemployment seen for West Michigan in April was a historic high — reflecting a spike of 20.4 percentage points from the rate of 2.9 percent recorded in March. The significant growth in regional unemployment observed over-the-month reflects a decline of 202,000 (-25.3%) in the number of employed residents from March to April, while the number unemployed rose by over 157,000 (653.0%). The net effect of the pandemic’s impact on the region’s labor force resulted in 44,600 labor force separations in April, indicating that over one-fifth of residents who experienced job loss over-the-month also disconnected from the labor force (either no longer seeking work, moved elsewhere, or recently deceased). With just 778,685 participants, the West Michigan labor force in April resembled the size seen at the onset of the Great Recession in 2007, while the size of the statewide labor force aligned more with levels recorded in 1991.

Goods-producing industries in West Michigan lost 44,600 jobs (-28.1%) while service-providing industries experienced a loss of 104,000 workers (-22.2%), compared to a -30.4 percent reduction for goods-producing industries statewide (-240,400 jobs) and -20.5 percent for service-providing industries (-737,300 jobs). This equates to an overall loss of 146,000 private-sector jobs for the 13-county region, capturing a negative growth rate of -25.7 percent, which slightly exceeds the statewide rate of -25.6 percent (-974,800 private-sector jobs).

As of April 2020, West Michigan workers averaged 33.1 hours per week, signaling a drop of 0.6 hours per week (-1.8%) from the average of 33.7 hours recorded in March. Yet, despite a sharp drop in the average number of hours worked, the average weekly earnings for West Michigan residents increased by $20.78 over-the-month — signaling the disparate impact of pandemic-related job loss concentrated among low-wage and comparatively lower-skilled occupations. However, without access to more granular information regarding occupational job-loss provided through our Statewide Longitudinal Data System (SLDS), we must wait until 2021 to even begin estimating how the pandemic will affect future occupational demand. Our analysis of Michigan’s SLDS fostered 7 recommendations to improve the quality and transparency of the state’s data system. If implemented, Michigan’s SLDS could report monthly job growth and loss across occupational groups and industries which allows for more accurate and timely understanding of the pandemic’s effect on the state’s labor market and informs statewide decision-makers to respond accordingly.

Subscribe for More

{{cta(‘be643ac7-73e2-40f6-a7b2-7c5927924bf4’)}}